see all jobs

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW: Peter Zumthor on the role of emotions in his work, his latest projects and those LACMA renderings

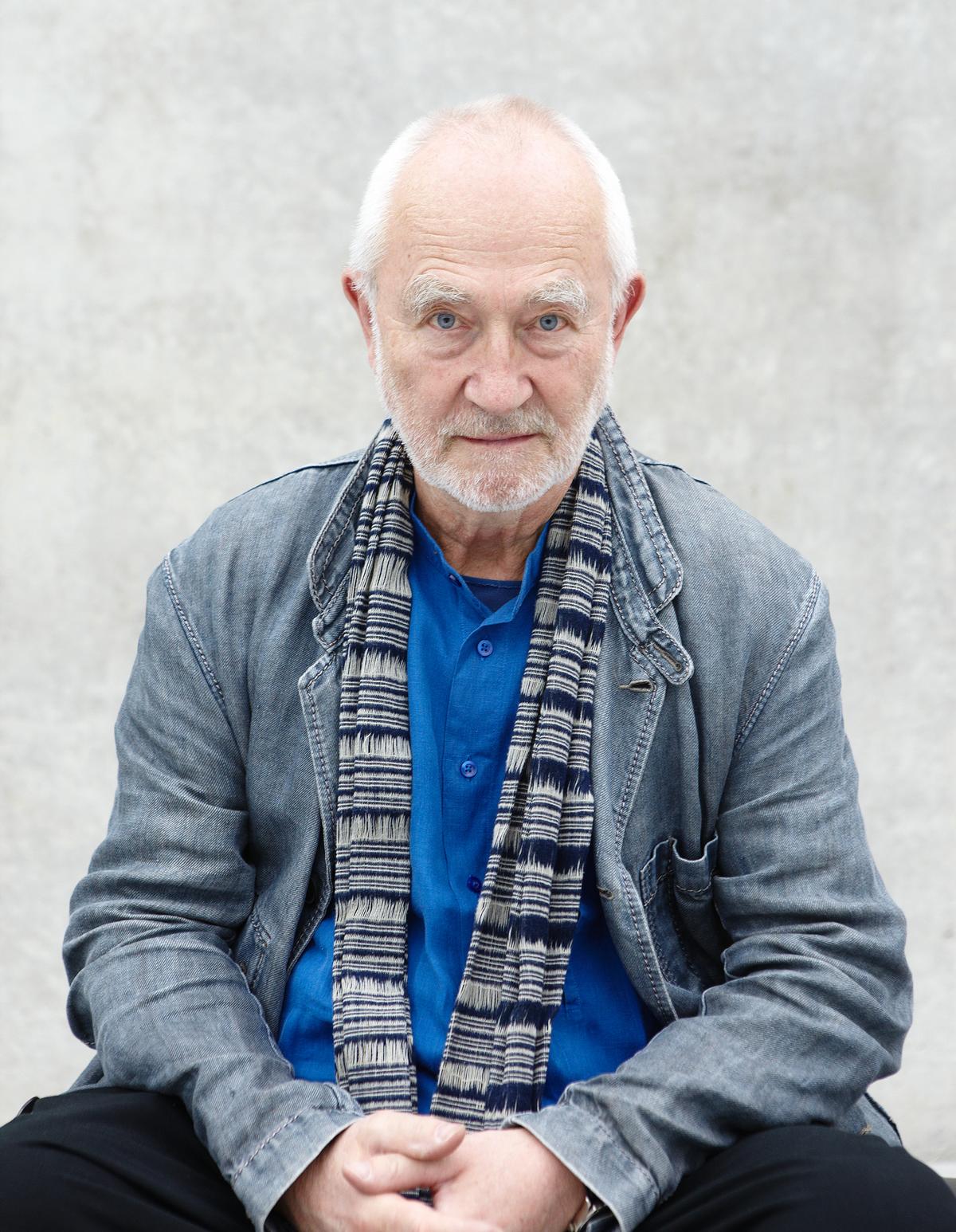

Creating buildings that inspire love is about more than just arranging and inventing forms, argues Peter Zumthor in an exclusive interview with CLAD. The influential Pritzker Prize-winning architect – who also runs through the latest on the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and his forthcoming projects in Korea, Germany, Switzerland and the UK – explains how his gift is to “see what’s ugly and doesn’t work in the world, and design things that do work.”

You can read the full feature below. The new issue of CLADmag – our quarterly magazine – is available to read now online and on digital turning pages.

CLAD editor Magali Robathan meets Peter Zumthor

I am waiting to meet Peter Zumthor in the Club Lounge at London's Langham Hotel. He is late, and I am a little apprehensive.

Zumthor is something of a cult figure within architecture. His body of work may be relatively small, but his influence is huge. He is known for his uncompromising approach to his work, for his craftsmanship and his careful use of materials and light, which can be seen in his best known projects, including the Therme Vals thermal baths in Switzerland, the Kunsthaus Bregenz art gallery in Austria and the Kolumba Diocesan Museum in Cologne, Germany. He has been awarded most of the top architectural prizes, including the Pritzker Prize and the RIBA Gold Medal, and is widely admired by his fellow architects, perhaps because he seems to have achieved what so many dream of – completing a small number of carefully-selected projects to his own high standards, with no apparent compromises.

He also operates a little differently to most architects of his stature. He doesn't have a global company with offices in London, New York or Zurich; instead he keeps his practice deliberately small, employing around 30 people, who work from a Zumthor-designed studio in the small town of Haldenstein in the Graubunden region of Switzerland. He doesn't have a website, he doesn't send press releases, he gives very few interviews and he won't speak to journalists on the phone.

When Zumthor finally arrives, he apologises, telling me that he has come straight from a meeting with his client, the director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). “We have been working intensively. That's why I'm late,” he says.

Zumthor is working on a $600m redevelopment of LACMA, which will see its ageing structures replaced by one large, organically-shaped building, designed to improve visitor flow, functionality and sustainability. It's Zumthor's first major project in the US, and arguably his largest to date.

I start by asking Zumthor how 2016 was for him. “Busy,” he says. “Full of work. It was a very successful year. I could do what I wanted to do; achieve, expand. Actually, for my health it was almost too much work. For at least half the year I was working seven days a week. Soon I will take a vacation.”

As well as the ongoing LACMA project, Zumthor completed the Allmannajuvet zinc mine museum in Sauda, Norway, in September, and was chosen to design an extension to Renzo Piano's Fondation Beyeler Art Museum extension in his home town of Basel. (“This is beautiful,” he says. “It warms my heart to be designing in the town I come from.”) He is also, he tells me, in the early stages of working on two projects in Korea – a small tea house and a large library, archive and exhibition centre– as well as a large scale park project in Munich.

TAKING IT SLOW

Early in the interview, I ask Zumthor a question. He pauses for a long time, and I make the mistake of interrupting him. He holds up his hand and gives me a stern look.

“Don't say anything!” he says. “I'm thinking! I like to take my time.” He pauses, and looks at me to check I've understood. I nod mutely.

“Okay,” he says, before continuing. This time, I keep quiet, and from this point on, the interview goes smoothly. He measures his words carefully, pauses after my questions to formulate his responses. I slow down to his pace, and I find it helps me to think about his answers, to tune into what he is really saying.

Zumthor is famous for his refusal to be rushed in his work, and has said that he doesn't want to make mistakes by building under a time pressure. I ask him later when a particular project will be finished. “It will take as long as it takes,” he says, simply.

Zumthor's list of completed projects is quite small in part because he takes his time over them, but also because he is very choosy about what he takes on. He is not, he tells me, driven by commercial opportunity.

“I'm a passionate architect,” he says. “Architecture as a business doesn't usually produce good pieces, because if you take it as a business, the result is to make good business, not to make good buildings.” But we all need money, I counter. He shrugs. “We've had times with little money, but I never suffered from that. I never had any serious money problems in my whole life, I've been lucky in that respect.

“Personally, I don't need a lot of money. Maybe for good wine.” He laughs.

“You shouldn't take architecture as a business, you should take it by its core – to try and make beautiful buildings, to be used well.”

STARTING OUT

Zumthor was born in 1943 in Basel, Switzerland, the son of a cabinet maker, Oscar Zumthor. The first buildings that really had an impact on him, he tells me, were the buildings of his youth. “My father's house, the first movie theatre I went to, churches, railway stations. I was experiencing architecture before I knew it was architecture.

“I think it’s so important where we grow up. It shapes our relationship to the world.

Zumthor initially trained as a cabinet maker, working alongside his father. “When I started in my father's shop at the age of 20, I wouldn't have dreamed of being an architect,” he says. “This was far away from my thinking, and the thinking of my family. My father once confessed to me that he would have liked to have been an architect, but his mother told him no, we have no money. You have to work'.”

In 1963, Zumthor attended the Kunstgewerbeschule school for applied arts in Basel, before studying industrial design at the Pratt Institute in New York. He then returned to Switzerland, and got a job as building and planning consultant and architectural analyst with the Department for the Preservation of Monuments in Graubünden. In 1978, he set up his own practice in Haldenstein, where he was living with his wife.

His first buildings were all in Switzerland and included several housing projects, a chapel, a small art museum and shelters for a Roman archaeological site. His first high profile project was the Therme Vals spa, built over naturally occurring thermal springs in Graubunden, Switzerland. The thermal baths opened in 1996, and remain one of Zumthor's best loved projects.

It's a beautiful structure, partly submerged into the mountain, built from layers of locally quarried quartzite stone. The combination of light, stone and water creates a quiet but powerful building that was designated as a national monument just two years after opening. “It was a beautiful opportunity to redefine bathing in a hot spring,” says Zumthor.

A year later, his Kunsthaus Bregenz project opened, overlooking Lake Constance in Austria. The glass, steel and cast concrete four storey museum has no visible windows; instead etched glass shingles allow diffused light to illuminate the artworks.

More projects followed, including the Kolumba Museum in Cologne, Germany. The building, which houses the art collection of the Catholic Archdiocese of Cologne, rises from the ruins of an old Gothic church destroyed during the Second World War.

“This was a beautiful opportunity for me to deal with the history of the place, to prove to myself that you can embrace the past and do something which grows out of it, as opposed to making a contrasting building which modern architects sometimes do,” says Zumthor.

Other projects have included a monument to 91 witches murdered during the 17th century on the island of Vardo in Norway, the 2011 Serpentine Gallery Pavilion in London, and an ongoing project to design a secular retreat in Devon, UK, as part of Alain de Botton's Living Architecture project.

It hasn't all been plain sailing, however. In 1993, Zumthor won a competition to design a museum and documentation centre of the Holocaust in the former Gestapo and SS headquarters in Berlin. Construction was stopped shortly afterwards to funding problems, and Zumthor has cited this as one of the biggest disappointments of his career.

LA COUNTY MUSEUM OF ART

In 2013, Peter Zumthor unveiled his designs for a new home for the LA County Museum of Art (LACMA). His design sees the existing LACMA buildings being demolished and replaced by an elevated, black, organically-shaped structure, inspired by the nearby La Brea tar pits.

A year later, Zumthor and LACMA revealed a revised design, following criticisms by local groups that the original proposals would put the tar pits at risk. The new plans keeps the original structure, but sees it straddling Wiltshire Boulevard instead of encroaching on the pits.

“In a few years, if you look at the building, I would hope you would say, 'ah, this building knows about the tar pits,” says Zumthor, of his aims for the new museum. “Maybe because it's black, maybe because of its organic form. I would like people to look at it and think maybe this building is much older than the other buildings there; that it belongs more to the ancient earth than to the other LA buildings.”

The starting point for the design, says Zumthor, were the objects displayed within the museum.

“The Los Angeles County Museum of Art is basically an encyclopaedic museum of art,” he says. “This means it has a web of objects and paintings. Many of these things were not made for the museum. They have lost their contacts; these objects; you could say they are homeless. I am creating a new home for the homeless objects where they can feel good in their new surroundings.”

It was important for Zumthor to tune into the objects themselves, he continues. “I trust the beauty of the object; I trust that they are telling me something. I’m interested in the feeling of history; the fact that before me there have been generations of people and they have made beautiful objects, and here they come to me. I hear the curators talking, but I trust the beauty of the objects first because explanations change.”

Zumthor's proposals incorporate eight, semi-transparent pavilions, which support the main exhibition level, with access points to the surrounding gardens. The design will also create two and half acres of new public outdoor space, including sculpture gardens, educational spaces and areas for flora and fauna that integrate with the surrounding parkland.

“The museum is not organised in timelines, periods or geographical regions,” he explains. “It's organised like a forest with clearings inside, where we have free choice to go to this clearing, or to the next. I would like to allow an experience of art where people can go and look at the art without didactics, without premature explanations, and make their own experience.”

“The museum is open to the outside; this is very important. You’ll have this almost sacred, sublime kind of experience, but I would also like to accommodate the profane, the dirty, the normal, the everyday.

“You start off down on the ground – this is normal city life – then as you go up you are received in a beautiful big palace for the people. From there you can go to the clearings, and that’s where you have the most intimate and maybe more private experiences of art."

In August 2016, new renderings of the Zumthor's planned LACMA redesign were released. The renders were criticised in some quarters, and Zumthor tells me he was not happy with them.

“These images were created for an environmental review. These are conventional, commercial-looking renderings, which I personally don't like so much,” he says, adding that his studio is currently working on photos taken from models prepared especially for the purpose. “The models allow us to take pictures with natural daylight, the light of the sun, which makes a lot of difference,” he said. “These will explain the building better.”

CREATING EMOTIONAL SPACES

Zumthor has said in the past that his ultimate goal is to “create emotional space” I ask him how he goes about doing this.

“I love buildings,” he says. “When I look back on my life I love the buildings that speak to me by means of their atmospheric qualities, by means of a feeling of history, of being complete.

“This is something basic in life. I look at a person and it’s nice if I could like or love them. It’s a beautiful feeling when I discover that this is a nice relationship. It’s how I experience buildings. In that I’m not alone - everyone shares this idea. I want to make buildings which have the capacity to be loved, that’s all. Nothing special.”

But how does he go about making those buildings, I ask. That's the special part.

“There are many levels,” he says. “As an architect you have to follow the technical levels, the urbanistic levels and so on, but the most important is probably a beautiful unity of use, atmosphere, space. So that the kitchen of my mother looks the kitchen of my mother and not like something strange. It’s about the real thing. That’s what I go for.

“I don’t treat the profession of architecture as a profession of arranging and inventing forms,” he continues. “You don’t hear anything from me like that. These things I want to do need a form, and so I give them this form. I’m extremely sensitive to things which don’t work.”

At this point, Zumthor gestures at the space behind me where the banquette seating meets the wall. “If I look over there and I don’t blur my eyes I can see ‘this meets this, this goes onto this…' I hate everything!” he says. “It’s so bad. Nobody ever cared about this space. Everything is bad...no taste, no talent, pure commerce.

“Many people see what’s ugly and doesn’t work in the world. I have skills and I have talent [to design things that do work]. That’s a gift. Like Roger Federer can play tennis, that’s a gift.” He laughs.

The next year should also be a busy one for Zumthor. As well as the LACMA project, he is working on designs for a multi million euro extension to the Beyeler Art Museum in Basel, Switzerland, which will add new exhibition and educational facilities to the existing Renzo Piano-designed building.

Other projects include a tea house in Korea, and a building housing a library, exhibition facilities and archives for the Korean poet Ko Un, also in Korea. Zumthor is also working on a large-scale project near Munich called Nantesbuch which he described as a “new form of landscape park. We will invite artists to show their art there, to make site-specific works. We might ask some of them, including myself, to create gardens. We are now in the conceptual stage for that project.”

I have been with Zumthor for around an hour, and he tells me that he has to go straight from our meeting to the airport, to fly back to Switzerland, to his studio in the mountains. Just before he leaves, I ask what his dream future commission would be.

“I would like to build something on the seashore,” he says. “I think the relationship to the sea is beautiful. I have done things with the relationship with the mountains, but not the long horizon of the sea...I like the water, the expanse. It makes me quiet.”

More News

- News by sector (all)

- All news

- Fitness

- Personal trainer

- Sport

- Spa

- Swimming

- Hospitality

- Entertainment & Gaming

- Commercial Leisure

- Property

- Architecture

- Design

- Tourism

- Travel

- Attractions

- Theme & Water Parks

- Arts & Culture

- Heritage & Museums

- Parks & Countryside

- Sales & Marketing

- Public Sector

- Training

- People

- Executive

- Apprenticeships

- Suppliers